Unit for the Search of Disappeared Persons (UBPD) Snapshot 2

Relatives of Missing Persons are the Key Actors for the Unit of the Search for the Disappeared

In Colombia, there is a long history of searching for the disappeared and records of forced disappearance date back to the 1950s. Several actors have focused on these searches. On the one hand, the Colombian state looks for those missing, through judicial institutions and the police. On the other hand, the families of disappeared persons, who suffer deeply from the absence of their loved ones and the injustice of it, lead their own initiatives for encountering them. In both cases, searches are founded on chasing down leads, and following clues and intuitions. For the state this means implementing a systematic search with logistical and technical support. In the case of relatives, searches are more erratic, marked by deep loneliness, uncertainty and risk, but families also have the ability to imagine new forms of encounters. This snapshot analyses the commitment of transitional institutions to putting family members at the centre of their work.

The UBPD’s commitment

The National Centre for Historical Memory has estimated there to be more than 80,000 direct victims of forced disappearance in Colombia and the Registry of Victims (RUV) reports more than 125,000 indirect victims. Given the high level of underreporting, these figures are approximate and could be higher. The Unit for the Search of Disappeared Persons (UBPD) was established as a result of the 2016 peace agreement. The unit has proposed a different approach to the search for the disappeared, giving a central role to the relatives and allowing them to feed their experiences and knowledge into the search process.

The UBPD has created spaces for dialogue with the relatives of disappeared persons. Family members are actively involved in these spaces, with their specific needs and requirements taken into account. The unit faces the complex challenge of fostering trust and tranquility with families through collective and collaborative processes. As a result, it has opened various communication channels that facilitate family members’ access to information on its processes, and on the general tasks of the unit. The UBPD has also developed and disseminated pedagogical tools on its web platforms and social networks. These aim to expand the participation of families by providing accessible information in different formats such as video podcasts, animations and information campaigns aimed at different groups of victims such as girls, boys and adolescents.

Victims acknowledge the focus shift

The UBPD’s different communication channels contain testimonies of people who, after years of searching for their loved ones, finally feel they are welcomed, supported, and no longer alone. Relatives recognise this is due to the ways they are able to get access to advice and information on the progress of investigations; the fact that their experiences and knowledge of searching for their disappeared ones are included in institutional processes; the opportunities that now exist for exiled victims or those who are part of the Colombian diaspora to participate; and the opportunity of having spaces that are both confidential but also collective, which allows families to be closer to those living through similar experiences.

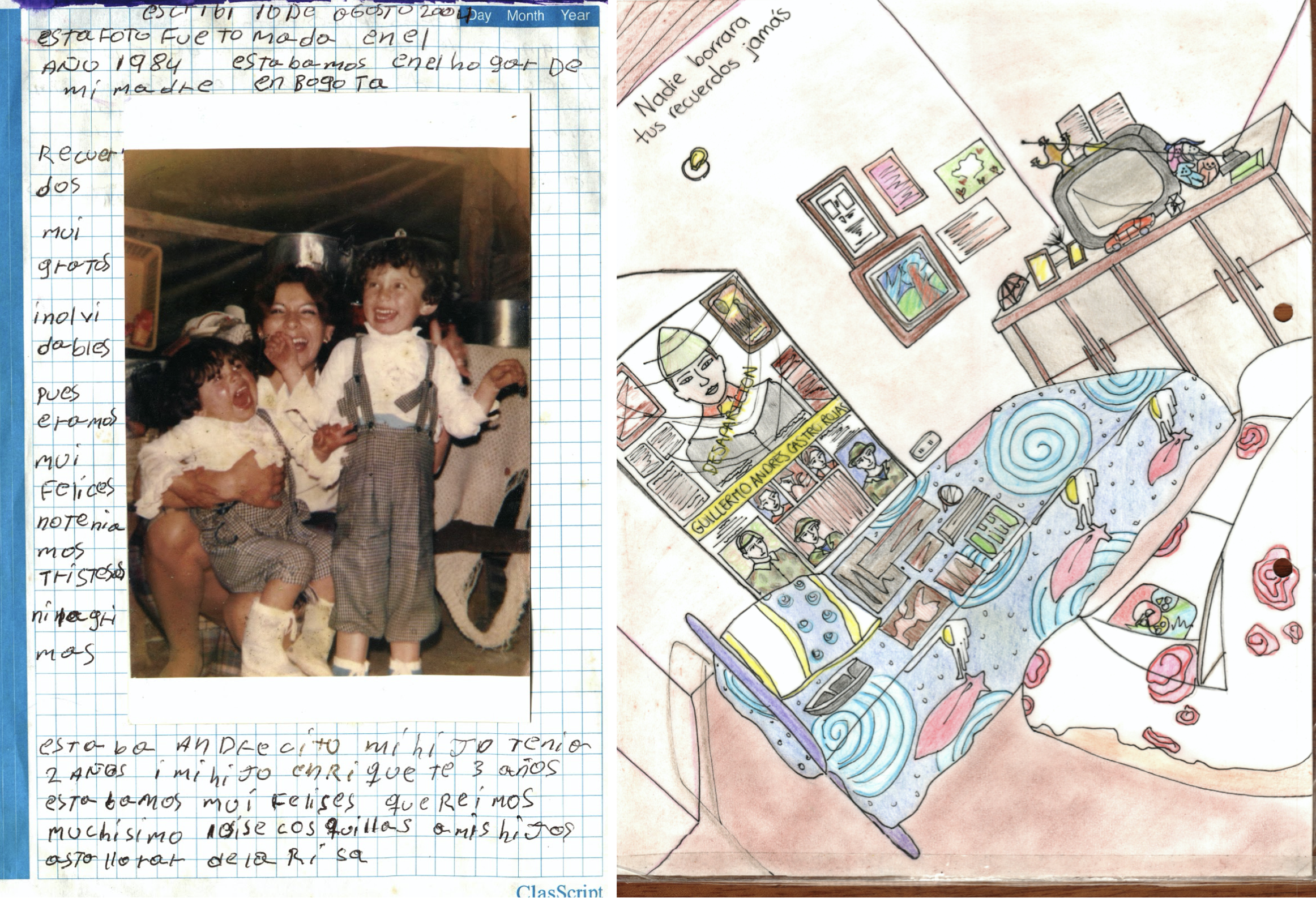

Left Image: Andres, Martha, and Enrique (1987) / Right Image: drawing of Andres’ room (2019) Photographs taken by María Ordoñez (2019)

Martha’s experience

Martha is the mother of Enrique and Guillermo Andrés. On October 1st, 2001, Andrés, her youngest son, received a call and left his home to meet someone in the street. Since then, Andrés became one of the many forcibly disappeared persons in Meta.

From 2001 until today, Martha has experienced waiting for her son by continuing to search for him through making journeys to rivers, meadows, and villages. She has also tackled this experience by writing and drawing, and through integrating her son’s objects and belongings into her daily life.

In 2019, after more than 18 years of searching and waiting, Martha saw the case of Andres’ disappearance accepted by the UBPD. This was achieved due to the efforts of the Nydia Erika Bautista Foundation, who have provided legal support to Martha since 2018.

For Martha, the UBPD’s work has been very different from that of any other government institution. In her own words, “My first encounter with the unit was in 2019. I remember that day I brought my Andresito’s book and photographs so that they would know all my history. They had taken my phone number, and a few days later called me for an interview. On the day of our meeting, we started at 9 am, and we finished at 3 pm. They listened to me almost the whole day.”

The UBPD’s access and communication channels have been key. “For me, all this work means a lot because for the first time I feel that a state institution is listening to me, and this makes me feel supported. I think this is so important for the mothers of disappeared persons.”

Regarding the search for her son and other disappeared persons, Martha says she has confidence in the work the unit has been doing so far and she believes that they will be able to identify many disappeared people and help so many families.

Andres’ room. Photograph taken by María Ordoñez (2017)

Embrace Dialogue (ReD) values the effort of the UBPD to put the relatives of disappeared people at the centre of their work and invites Colombian society to recognise the reparative value this has for thousands of people who, like Martha, now feel recognised.

Biden y Harris (Tomada de: New York TImes - ReduxStock)

Biden y Harris (Tomada de: New York TImes - ReduxStock)