Can the triumph of the left in the presidential elections pave the way for reconciliation in Colombia? Andrei Gómez-Suárez analyses the results of the March congressional and primary elections and outlines the challenges for reconciliation in the case of a Petro presidency.

Is reconciliation possible after the elections of 13 March 2022? In a previous piece I argued that a breakthrough for reconciliation in Colombia was still possible. However, the results and developments since the March elections are bittersweet, as is common in long and complex processes of reconciliation.

Congressional Elections: one step forward, two steps back?

The March elections brought positive outcomes. First, a high participation in the polling stations; the participation rate was 45.87%, which is only 3% less than 2018. Second, more than 25 social leaders and youth were elected for the first time as Congress members: for example, Maria Fernanda Carrascal, Jahel Quiroga, and Jonathan Pulido Hernandez. Third, eight of the sixteen special peace constituencies —seats created by the 2016 peace accord with the intention of increasing political participation of the most conflict-affected regions— went to representatives of victims’ organisations. Fourth, the Pacto Histótico (Historic Pact), Gustavo Petro’s political coalition, obtained 3 million votes in the primary consultation, a record number for a leftist coalition, never before seen in the history of Colombia, showing that the fear of the left is fading, at least amongst some sectors of Colombian society.

However, there were also negative results. First, traditional political families, such as the Gnecco in Cesar, the Pacheco in Caquetá and the Blel in Bolívar, maintained their hold over 26% of the seats in Congress. Second, anti-peace agreement politicians, such as Paloma Valencia, María Fernanda Cabal and Paola Holguín, won a substantial number of votes – Cabal was the most voted woman with 127,399 votes. Third, the electoral participation in conflict-affected areas was low; the abstention rate reached 57% in some regions due to the lack of security guarantees and the participation of traditional political parties in the special peace constituencies, despite the fact that legally these seats are not supposed to be represented by existing political parties.

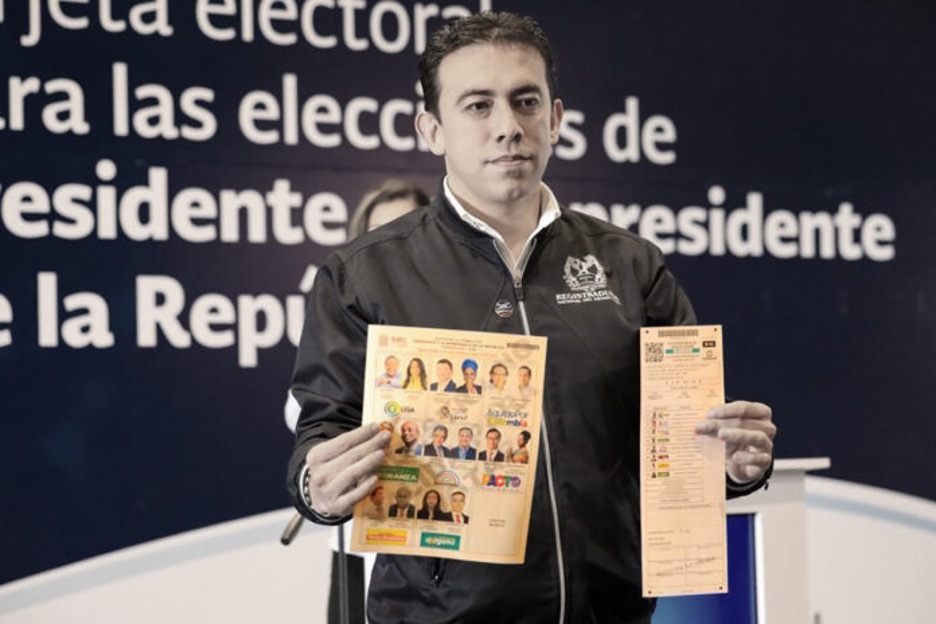

In May 2022, two months after the elections, Colombia still does not have clarity on the final composition of Congress. The uncertainty about the results has been blamed on Alexander Vega, Director of the National Registry Office, the institution in charge of counting the votes. The National Registry took four controversial decisions: first, it changed the majority of electoral judges just before elections; second, it carried out a short last-minute training of these new electoral judges; third, a pre-count form was identified by the Electoral Observation Mission as containing a mistake that was deemed to make it probable that votes for the Pacto Histórico would not be counted, yet the National Registry Office failed to modify these forms; and fourth, it procured a software program which collapsed on election day. Petro claims that his coalition has identified so far over 700,000 votes that were stolen from his coalition in the March elections, which have now been recovered by lawyers who challenged the results.

The National Registry’s deficient performance has nurtured the widespread fear of fraud, thereby hampering reconciliation. It has helped reinforce the untrustworthiness between sectors who see Colombia as divided between left vs right, pro-peace vs anti-peace, populist vs democrats, neoliberal vs communists, and technocrat vs charlatans. Now, a new division is emerging between those who defend the legality of the election of the largest leftist Congress coalition in the history of Colombia vs those who think it is the product of fraud. For a country with a long history of political violence this division is extremely dangerous, because it opens the possibility of violence if the left wins the presidential elections, if detractors argue that the results are the product of fraud.

The last four years in Colombia prove that political violence is not a matter of the past. The return to war is always a possibility in societies on the path to reconciliation. Peace, which is concomitant with reconciliation, is political; let us remember that according to Prussian general, Carl von Clausewitz “war is merely the continuation of politics by other means.” Therefore, peacebuilders must strive to weave multisectoral alliances that make the return to war less likely. Congressmen and women are a key sector in these alliances because they link policy with regional actors and can legislate peace policies demanded by society and ensure its active participation.

Colombia elected a broad spectrum of congress members who support pro-peace agendas, but they are not a majority in Congress yet. They will likely manage to build alliances with traditional parties, whose members usually accommodate to circumstances to profit from public funds, but these coalitions are not stable because in the following elections they usually ally with the best bidder. However, according to recent reports, there will be 40 pro-peace senators this period of 2022-2026, and this number may continue to rise, as indeed it did between 2018 and 2022, when the first congress in charge of implementing the peace agreement was acting. Over the next four years, Congress can give oxygen to reconciliation in Colombia, and this could change the balance of power in Colombian politics for the elections to come.

The Presidential Primaries: A Black Swan in the making?

The Colombian primaries also took place in March, to select the presidential candidates for left, centre, and right-wing coalitions. The centrist committed with peace implementation received the least number of votes across all the primaries, under the leadership of Sergio Fajardo; the right-wing coalition, which criticizes the transitional justice mechanism, in particular the Peace Tribunal, and the role of the FARC in peace implementation came second and elected Federico (“Fico”) Gutiérrez; and the left, which has committed to go beyond peace implementation and bring about structural reforms for marginalized sectors of society won first place with former M-19 guerrilla member Gustavo Petro.

The results have unleashed a nasty political campaign and show the challenges for reconciliation today. Three campaign strategies have deepened the divisions between Colombians: the first, an anti-Petro strategy; the second, an anti-extremes strategy; and third, an anti-Fico message (linking existing anti-Duque and anti-Uribe narratives). People trapped in these strategies are seen as traitors if they try to move away from the demonisation of the other(s). The tensions inside these three camps are huge: the left is divided between those who promote pragmatism vs those who stand for dogmatism; the right is divided between those who defend authoritarianism vs those who are willing to move towards a limited democracy, and the centre is torn between those who stand for purist anti-traditional politics vs those who acknowledge the need to compromise in order to win.

Opinion polls carried out in May, two months after the elections, show that despite the anti-Petro campaign, the support for Petro continues to grow (today reaching 40%), that Gutiérrez is second despite the anti-Uribe/Duque/Fico narratives (today he has 25% in the polls), and that Fajardo is third despite his anti-extremes campaign message (today the polls rank him as low as 7%). Unexpectedly, Rodolfo Hernandez, who did not participate in the primaries as he is not running on a coalition, stays steady at 13%, capturing the imaginary of the centrist voters that Fajardo is steadily losing. In this scenario, the alliance between pro-peace sectors scattered across these three camps seems even more distant than four years ago, when Duque won the elections. Colombians feel enmeshed in polarisation, which seems to be a wall in the journey towards reconciliation.

However, the history of humanity is full of quantum leaps, highly improbable events that change the course of social processes forever. American Lebanese writer Nassim Taleb calls these events “Black Swans”. According to him, once the unthinkable occurs, it is quickly integrated in common sense, and people accept it as inevitable, without paying careful attention to the lessons learned. Taleb’s metaphor comes from the fact that in Europe up until 1697 it was believed that all the swans were white. When Dutch explorer Willem de Valmingh reported seeing the first black swan in Australia, what had previously seemed impossible became possible, and thus an apparently universal law changed radically from one moment to another. According to Taleb, the challenge is that these highly improbable events cannot be predicted, and nor can their effects, as was the case, for example, in the attack on the World Trade Centre in September 2001.

In 2012, it was desirable but still unthinkable that the Colombian government could sign a peace agreement with the FARC, but such a Black Swan occurred in 2016. Today, despite the opinion polls, many people consider a leftist government in Colombia to be unthinkable, and many are worried that an eventual presidency of Petro will further polarise Colombian society. We cannot predict if this will happen, nor calculate its impact on reconciliation, just as the peace agreement with the FARC was unexpected and the impact of its implementation is to a significant extent incalculable. However, it must be noted that the only candidate who is talking about forgiveness is Petro. Among many other international supporters, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, former Prime Minister of Spain, believes in his desire to reconcile Colombian society.

It remains to be seen whether a Black Swan will emerge from the presidential elections in Colombia, and whether a broad sector of Colombians, those who do not tend to participate in politics, could take unpredictable decisions. If this happens, the Pacto Histórico could be the Black Swan that changes forever the journey towards reconciliation in Colombia.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!